Jaws and the Shark You Don't See

- Daniel Marion

- Dec 11, 2025

- 5 min read

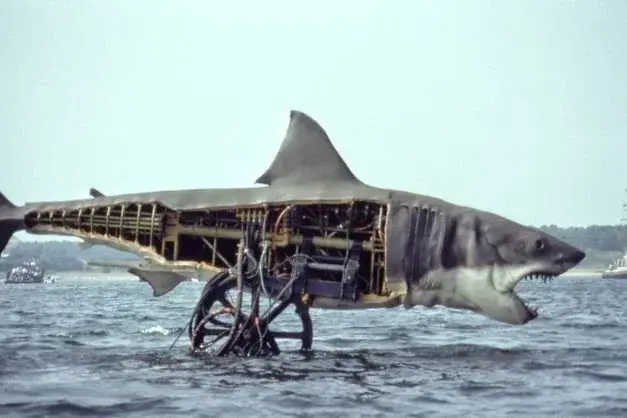

Steven Spielberg almost quit filmmaking because of a mechanical shark.

It's 1974. He's 27 years old, directing his first major studio film. The budget is ballooning. The shoot is a nightmare. And the mechanical shark—nicknamed "Bruce"—keeps breaking down.

It won't surface on cue. The salt water corrodes the mechanisms. The thing looks fake in broad daylight. Spielberg is panicking. The studio is furious. The crew is exhausted.

And then, out of sheer desperation, Spielberg makes a decision that changes everything:

If the shark doesn't work, don't show the shark.

That constraint—that limitation that felt like a disaster—became the reason Jaws is a masterpiece.

Because here's the truth: the shark you don't see is way more terrifying than the shark you do.

Welcome to Dan's World

The Power of Suggestion

Let's talk about what Spielberg did instead of showing the shark.

He showed the effects of the shark.

A yellow barrel being dragged through the water

Panicked swimmers scrambling to shore

The iconic two-note theme building tension (dun-dun... dun-dun... dun-dun)

A pier being ripped apart from below

Blood in the water

You don't see the shark for over an hour. But you feel it. You know it's there. You're terrified of it.

And when you finally do see it—briefly, strategically—it's more impactful because you've spent the entire movie imagining it.

That's the power of suggestion. Your brain fills in the gaps. And what your brain imagines is almost always scarier, more intense, more memorable than what a camera can show you.

Spielberg didn't plan it that way. He was forced into it by a broken mechanical shark and a ticking clock.

But that constraint made the film legendary.

What Jaws Teaches Us About Creative Work

Here's the lesson every creative professional needs to internalize:

Limitations don't ruin your work. They force you to focus on what actually matters.

When you can't rely on spectacle, you have to rely on craft. On storytelling. On building tension, creating atmosphere, and trusting your audience to engage with what you're giving them.

Spielberg couldn't show the shark, so he had to make you feel the shark. And feeling is always more powerful than seeing.

I see this all the time in video editing. A client will say, "We don't have much footage," or "We couldn't get the shot we wanted," and they're worried the project won't work.

But often, that's when the best work happens.

Because when you can't rely on having everything, you get creative with what you do have. You focus on pacing. On music. On the emotional arc. On building anticipation instead of just showing everything upfront.

The constraint forces you to be better.

The Art of What You Don't Show

One of the most important skills in any creative field is knowing what not to include.

In video editing, it's knowing which clips to cut. In writing, it's knowing which sentences to delete. In design, it's knowing when to leave white space.

And in filmmaking, it's knowing when to hold back.

Jaws works because Spielberg understood that mystery creates tension. The moment you see the full shark in bright daylight, the spell is broken. It's just a mechanical prop. But when you only see glimpses—a fin, a shadow, the destruction it leaves behind—your imagination does the heavy lifting.

The same principle applies to almost any creative work:

A website doesn't need to explain everything on the homepage. Give people just enough to be intrigued, then let them explore.

A video doesn't need to show every detail. Sometimes a close-up, a reaction shot, or an implied moment is more powerful than showing the whole thing.

A voiceover doesn't need to spell out every point. Leave room for the audience to connect the dots.

What you leave out is just as important as what you include.

And that's a hard lesson to learn, because our instinct is always to add more. More information. More footage. More explanation.

But the best work often comes from subtraction, not addition.

When Constraints Become Your Advantage

Here's the thing about Jaws: if the mechanical shark had worked perfectly, Spielberg probably would have shown it constantly. And the movie would have been fine. Maybe even good.

But it wouldn't have been Jaws.

It wouldn't have had that relentless, creeping dread. It wouldn't have made an entire generation afraid to go in the water. It wouldn't have become the blueprint for every thriller that came after it.

The broken shark forced Spielberg to be smarter. To be more strategic. To trust the audience's imagination.

And that's the paradox of creative constraints: they feel like obstacles, but they're often the thing that makes your work great.

I've had projects where I didn't have the footage I wanted, or the timeline was too tight, or the budget didn't allow for what I originally envisioned.

And you know what? Some of my best work came from those projects.

Because I couldn't rely on having everything, I had to make choices. I had to prioritize. I had to figure out what the story really needed, and cut everything else.

👉 Constraints force clarity. And clarity is what separates good work from great work.

The Lesson for Your Work

So here's the question I want you to ask yourself:

What's your broken shark?

What limitation are you facing right now that feels like a problem? Not enough budget? Not enough time? Not enough resources?

What if that's not the obstacle you think it is? What if it's actually the thing that's going to force you to do your best work?

👉 Because here's the truth: you don't need everything. You just need to use what you have with intention.

Spielberg didn't need a working shark. He needed suspense, atmosphere, and a story that kept people on the edge of their seats.

You don't need unlimited footage, infinite time, or a massive budget. You need a clear goal, smart choices, and the discipline to focus on what actually matters.

Why This Still Matters

Jaws came out in 1975. Fifty years later, it's still studied in film schools. Still referenced in every conversation about suspense and tension. Still one of the greatest examples of turning a limitation into an advantage.

And the reason it still matters is because the lesson is universal:

🤯 Great work doesn't come from having everything. It comes from using what you have in the smartest way possible.

Whether you're editing a video, building a website, writing copy, recording a voiceover, or creating anything else—the principle is the same.

You don't need to show everything. You don't need to explain everything. You don't need to have every resource at your disposal.

You just need to understand what your audience needs to feel, and then build toward that with everything you've got.

The Shark You Don't See

So the next time you're facing a creative limitation—when the thing you planned isn't working, when you don't have what you thought you needed, when the project feels impossible—remember the mechanical shark that wouldn't surface.

And remember that sometimes, the best creative decision you can make is to show less, suggest more, and trust your audience to fill in the rest.

👉 Because the shark you don't see? That's the one that stays with you long after the credits roll.

What about you? What's a creative constraint that forced you to do better work? I'd love to hear your "broken shark" story.

Comments